| Guide | ♦ | 28 Triplogs | 3 Topics |

details | drive | no permit | forecast | 🔥 route |

stats |

photos | triplogs | topics | location |

| 587 | 28 | 3 |

Prehistoric and Historic Ruins by Randal_Schulhauser  Note NoteDec 2015 gate reported locked and barbed wired. History President Bill Clinton created the Agua Fria National Monument in 2000 at the behest of his Secretary of the Interior, former Arizona Governor. Bruce Babbitt. For most people zipping along the Interstate, they're probably scratching their heads looking at the big empty spaces wondering why this area has been declared a National Monument. One answer to the "Why?" is "Abundant prehistoric and historic period ruins." This hike offers an opportunity to experience both. From about 1200 to the mid-1400's a thriving "mesa-canyon complex" culture inhabited the area leaving 400+ known archeological sites. The Perry Mesa Tradition featured "seven ancient cities" supported by a number of "satellite" settlements. Richinbar Pueblo represents one of these "satellite" settlements, featuring about 65 rooms, at least 2 rock art clusters, and countless pottery sherds.

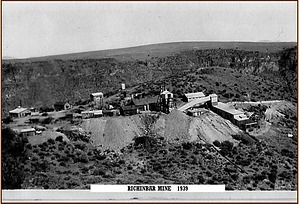

Original prospecting claims for Richinbar Mine were filed upon discovery in 1882, but it wasn't until 1896 that commercialization began in earnest. A post office opened that year with the name "Richenbar" - a derivative of Richard N. Barker, one of the mining camp's leading citizens. A Prescott News article dated August 28, 1897 indicated that Richinbar had phones, electricity, plus daily stage service. As researchers Neal Du Shane and Pat Ryland have documented, this news article also tells of the death of one of the miners, Ed Barden. He was killed on August 21st, 1897 when he was getting out of the mine, had a heart attack, and fell off a ladder into the shaft just as some TNT detonated. "The body was interred on the hill above the mine." A 20-stamp mill was added in 1906, and workings now featured the Zyke shaft (main shaft) at 500 feet deep that connects with several thousand feet of workings extending northward plus two more shafts accessing upper workings. The largest stope was on the 140 level at 65 feet long by 55 feet high and 14 feet wide. Employment at the mine grew to 35 workers by 1935. A Big Bug News article dated March 10, 2009 contains an interview with a former Richinbar resident, Anita Wheeler Underwood, who spent her teenage years in the mining community; "In 1936 the Wheelers packed up and left a comfortable home in Houston TX and moved to Richinbar AZ. Mr. Wheeler went to work at the mine, and Nita and twin brother Bud spent their first fall through spring in Phoenix attending school. Shortly after returning to Richinbar that spring of '37, the mine shut down. Everyone left but us. The electricity shut off, and since the water had to be pumped up from the river, there was no water either." The Richinbar Mine slowly emerged from bankruptcy and re-opened in 1940 and continued operation by the Sterling Gold Mining Company until 1948. Richinbar mining production as recorded for the period 1905 - 1948 by the Arizona Department of Mines and Mineral Resources; Cumulative totals are: Tons of ore 31,833 Pounds of copper 7,352 Pounds of lead6,947 Troy oz. of gold4,616 Troy oz. of silver1,425 Hike Armed with a GPS track posted on the "Arizona Pioneer and Cemetery Research Project" by Neil Du Shane, we found ourselves at the FR9006 trail head just off the I-17 on a perfect December morning. Parking at the gate seems to be your only option as it is locked (rancher and forest service access only?). Squeeze between the gate and post and begin your hike along the dirt road. The Bradshaw Mountains provide your backdrop to the west. In front of you lies our first hiking trail POI - the Richinbar windmill and corral. Continue on an easterly heading along FR9006 about 1 mile until the Agua Fria Canyon comes into view. The dirt road will bend slightly right to the southeast and begin a gentle decent of about 100 feet. As the dirt road comes to a "T-intersection" near the lip of the Agua Fria Canyon, there are multiple pioneer graves on both sides of the road as reported by the "Arizona Pioneer and Cemetery Research Project" (see map). We take the south fork of the dirt road and discover some historic period "sherds". Spotted our first shaft on the west side of the dirt road in an area that appears to have been surface mined. With a reported shaft depth of 500 feet, our "tests" give us no reason to doubt that number. A few feet further south, an isolated chimney points the route up a small hill top capped with an earthen water tank. This elevated water tank created the water pressure used in the mining operations. From this high point, you can easily spot the stamp mill and Zyke main shaft head frame foundations lying to the northwest. You can easily picture the head frame location relative to the main shaft. Tailings are everywhere. Mike and I contour down to the foundations and try to match each to the vintage photos we are carrying. Large stamp mill elements become clear to us. We're perplexed by the large number of trashed cans (gasoline? Kerosene?) we find littered about the site. Having fully explored the central mining operations, we retrace our steps along the dirt road heading north towards the petroglyph site. These are easily spotted - look for the elevated cluster of boulders. Deer and antelope seem to be the subjects for most of this rock art. Next up is Richinbar Pueblo located on the high ground just west of the Richinbar townsite and slightly north of the central mining operations. There is much rock art surrounding the walled area of the pueblo. I suspect there is another ruins site nearby. I had two photos with me labeled "Richinbar Pueblo" taken on past Arizona Archeological Society field trips. One certainly matches up with the site we explored. The second photo doesn't seem to match any of the landmarks! We found a faint doubletrack heading southwest from the looped dirt road. We spotted a sign at the canyon lip and charged over to it expecting to see more ruins. This was only a geological survey marker. We continued along the double track until it abruptly ended at what must have been a Richinbar dumpsite. Tin cans and porcelain remnants everywhere - a historic period midden! From the dumpsite, we took a cross-country cowpath over to FR9006 back to the trailhead. Summary: I've always wondered why vehicles were parked just off of the I-17 near a windmill on the mesa. A little research and I discovered the name "Richinbar" and multiple references about a bustling little mining community that disappeared 60 years ago. Step back in time and rediscover "Richinbar" on this hike, Enjoy! Gate Policy: If a gate is closed upon arrival, leave it closed after you go through. If it is open, leave it open. Leaving a closed gate open may put cattle in danger. Closing an open gate may cut them off from water. Please be respectful, leave gates as found. The exception is signage on the gate directing you otherwise. Check out the Official Route and Triplogs. Leave No Trace and +Add a Triplog after your hike to support this local community. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Route Editor

Route Editor